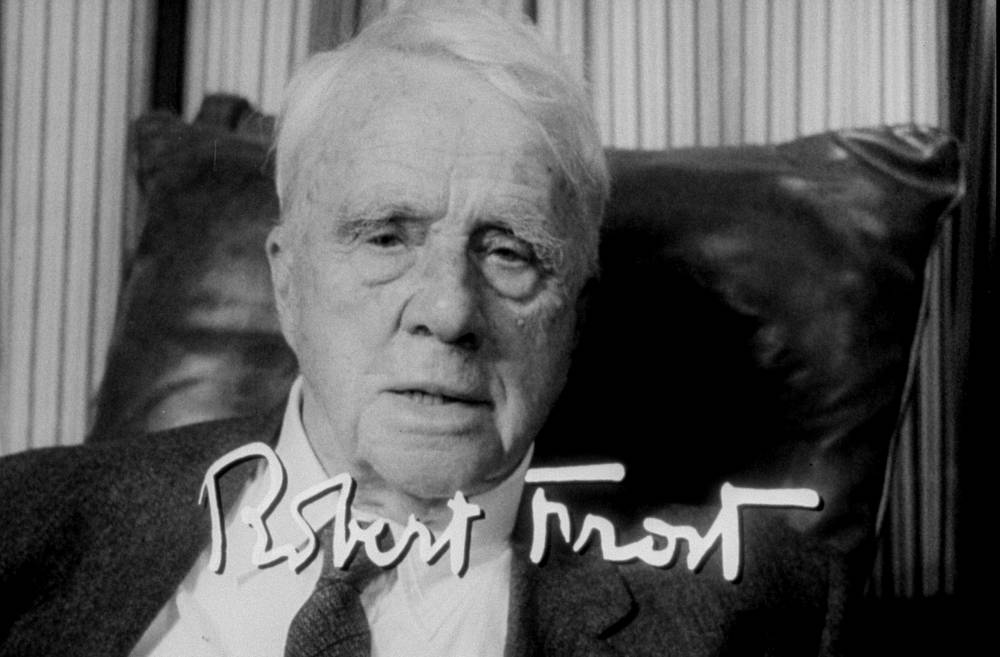

Robert Frost is a captivating poet and public figure whose approachability and mystique will assuredly engross many generations of scholars, whether their approach is biographical, cultural, or theoretical. Frost’s portions, inscriptions, and random poems will continue to surface until nearly all of the items in small, private collections find their way into shared annals. They in fact add enormously to our interpretation of how Frost worked through his ideas. Paired with poems or excerpts from Frost’s works, these repeatedly sumptuously and lavishly created greetings raise captivating questions about the interaction between the visual and the verbal in Frost’s work.

Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening is a poem by Robert Frost, published in the collection New Hampshire (1923). One of the most famous, as well as one of the most anthologized, of Frost’s poems. It portrays a lone traveler in a horse-drawn carriage who is both driven by the business at hand and mesmerized by a frosty woodland setting. The poem is written of four iambic tetrameter quatrains, and the contemplative lyric derives its incantatory tone from an interlocking rhyme scheme of aaba bbcb ccdc dddd:

Whose woods these are I think I know.

His house is in the village though;

He will not see me stopping here

To watch his woods fill up with snow.

My little horse must think it queer

To stop without a farmhouse near

Between the woods and frozen lake

The darkest evening of the year.

He gives his harness bells a shake

To ask if there is some mistake.

The only other sound’s the sweep

Of easy wind and downy flake.

The woods are lovely, dark and deep,

But I have promises to keep,

And miles to go before I sleep,

And miles to go before I sleep.

No American poet has been more prosaic than Robert Frost—prosaic because many readers like to believe most of his poems are narrative in nature, not just the lyrical representation of an image or a feeling.

Eternity Looking through Time

.jpg) Frost’s poem has the back drop of a late dark wintry sundown, a harsh and bitter winter (“The darkest evening of the year”). The physical setting of the work is the deserted woods far off from the village. The significance along with physical landscapes of the poem is dreadfully isolated, bare of any living flowers or leafy trees. The narrator of “Stopping by Woods” is compelled to make a significant ethical choice, which his cherished horse does not seem to concur with. The preference that the narrator must grapple with is whether to return to the cordiality and safety of the village (where the owner of the woods lives) and his home or to stay and watch the beautiful woods filling up with fluffy snowflakes on a wintry evening. The narrator does seem to have trouble making his decision, torn between two equally enticing and delightful possibilities. This kind of persistence upon human choice is distinctive of most of Frost’s poetical works. The narrator eventually chooses to return to the village even though it seems to take his great self-control or willpower. He understands that he has some social or civic duty or responsibility to achieve before he dies.

Frost’s poem has the back drop of a late dark wintry sundown, a harsh and bitter winter (“The darkest evening of the year”). The physical setting of the work is the deserted woods far off from the village. The significance along with physical landscapes of the poem is dreadfully isolated, bare of any living flowers or leafy trees. The narrator of “Stopping by Woods” is compelled to make a significant ethical choice, which his cherished horse does not seem to concur with. The preference that the narrator must grapple with is whether to return to the cordiality and safety of the village (where the owner of the woods lives) and his home or to stay and watch the beautiful woods filling up with fluffy snowflakes on a wintry evening. The narrator does seem to have trouble making his decision, torn between two equally enticing and delightful possibilities. This kind of persistence upon human choice is distinctive of most of Frost’s poetical works. The narrator eventually chooses to return to the village even though it seems to take his great self-control or willpower. He understands that he has some social or civic duty or responsibility to achieve before he dies.

The night, as well as the winter, is closely related to old age, pain, loneliness, and death. As stunning as snow looks, it implies the cold wintry weather, which is in turn connected with despair, disintegration, and death. Just as the woods are “lovely, dark and deep” to him, so does death look to him. Death seems not to be so unnerving, grim, or even scary—but rather fascinating, welcoming, almost a feeling of relief. The narrator is reminded of the final destination of his journey—probably to the village where his home is. The narrator’s “little horse” is perplexed by his master’s conduct —stopping by the woods located far away from any farmhouse—and thus jiggles his harness bells in impulsiveness. Impatient, the horse prompts him to resume his homeward journey.

“My Best Bid for Remembrance”

In a message to American poet, anthologist, and literary critic Louis Untermeyer, American poet Robert Frost called his famous poem “Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening” as “my best bid for remembrance.”

According to an essay by N. Arthur Bleau, Robert Frost described the poem’s back-story during a reading at Bowdoin College in 1947:

Robert Frost revealed his favorite poem to me. Furthermore, he gave me a glimpse into his personal life that exposed the mettle of the man. I cherish the memory of that conversation, and vividly recall his description of the circumstances leading to the composition of his favorite work.

We were in my hometown—Brunswick, Maine. It was the fall of 1947, and Bowdoin College was presenting its annual literary institute” for students and the public. Mr. Frost had lectured there the previous season; and being well received, he was invited for a return engagement.

I attended the great poet’s prior lecture and wasn’t about to miss his encore—even though I was quartered 110 miles north at the University of Maine. At the appointed time, I was seated and eagerly awaiting his entrance—armed with a book of his poems and unaware of what was about to occur.

He came on strong with a simple eloquence that blended with his stature, bushy white hair, matching eyebrows, and well-seasoned features. His topics ranged from meter to the meticulous selection of a word and its varying interpretations. He then read a few of his poems to accentuate his message.

At the conclusion of the presentation, Mr. Frost asked if anyone had questions. I promptly raised my hand. There were three other questioners, and their inquiries were answered before he acknowledged me. I asked, “Mr. Frost, what is your favorite poem?” He quickly replied, “They’re all my favorites. It’s difficult to single out one over another!”

“But, Mr. Frost,” I persisted, “surely there must be one or two of your poems which have a special meaning to you—that recall some incident perhaps.” He then astonished me by declaring the session concluded; whereupon, he turned to me and said, “Young man, you may come up to the podium if you like.” I was there in an instant.

We were alone except for one man who was serving as Mr. Frost’s host. He remained in the background shadows of the stage. The poet leaned casually against the lectern—beckoning me to come closer. We were side by side leaning on the lectern as he leafed the pages of the book.

“You know—in answer to your question—there is one poem which comes readily to mind; and I guess I’d have to call it my favorite,” he droned” in a pensive manner. “I’d have to say ‘Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening’ is that poem. Do you recall in the lecture I pointed out the importance of the line “The darkest evening of the year’?” I acknowledged that I did, and he continued his thoughtful recollection of a time many years before. “Well—the darkest evening of the year is on December twenty-second—which is the shortest day of the year—just before Christmas.”

I wish I could have recorded the words as he reflectively meted out his story, but this is essentially what he said.

The family was living on a farm. It was a bleak time both weatherwise and financially. Times were hard, and Christmas was coming. It wasn’t going to be a very good Christmas unless he did something. So—he hitched up the wagon filled with produce from the farm and started the long trek into town.

When he finally arrived, there was no market for his goods. Times were hard for everybody. After exhausting every possibility, he finally accepted the fact that there would be no sale. There would be no exchange for him to get a few simple presents for his children’s Christmas.

As he headed home, evening descended. It had started to snow, and his heart grew heavier with each step of the horse in the gradually increasing accumulation. He had dropped the reins and given the horse its head. It knew the way. The horse was going more slowly as they approached home. It was sensing his despair. There is an unspoken communication between a man and his horse, you know.

Around the next bend in the road, near the woods, they would come into view of the house. He knew the family was anxiously awaiting him. How could he face them? What could he possibly say or do to spare them the disappointment he felt?

They entered the sweep of the bend. The horse slowed down and then stopped. It knew what he had to do. He had to cry, and he did. I recall the very words he spoke. “I just sat there and bawled like a baby”—until there were no more tears.

The horse shook its harness. The bells jingled. They sounded cheerier. He was ready to face his family. It would be a poor Christmas, but Christmas is a time of love. They had an abundance of love, and it would see them through that Christmas and the rest of those hard times. Not a word was spoken, but the horse knew he was ready and resumed the journey homeward.

The poem was composed some time later, he related. How much later I do not know, but he confided that these were the circumstances which eventually inspired what he acknowledged to be his favorite poem.

I was completely enthralled and, with youthful audacity, asked him to tell me about his next favorite poem. He smiled relaxedly and readily replied, “That would have to be ‘Mending Wall.’ Good fences do make good neighbors, you know! We always looked forward to getting together and walking the lines—each on his own side replacing the stones the winter frost had tumbled. As we moved along, we’d discuss the things each had experienced during the winter—and also what was ahead of us. It was a sign of spring!”

The enchantment was broken at that moment by Mr. Frost’s host, who had materialized behind us to remind him of his schedule. He nodded agreement that it was time to depart, turned to me and with a smile extended his hand. I grasped it, and returned his firm grip as I expressed my gratitude. He then strode off to join his host, who had already reached the door at the back of the stage. I stood there watching him disappear from sight.

I’ve often wondered why he suddenly changed his mind and decided to answer my initial question by confiding his memoir in such detail. Perhaps no one had ever asked him; or perhaps I happened to pose it at the opportune time. Then again—perhaps the story was meant to be related, remembered and revealed sometime in the future. I don’t know, but I’m glad he did—so that I can share it with you.

Two Minds About It

.jpg) Frost’s daughter Lesley later validated the narrative and quoted her father reminiscing his weeping, “A man has as much right as a woman to a good cry now and again. The snow gave me shelter; the horse understood and gave me the time.”

Frost’s daughter Lesley later validated the narrative and quoted her father reminiscing his weeping, “A man has as much right as a woman to a good cry now and again. The snow gave me shelter; the horse understood and gave me the time.”

For many years I have assumed that my father’s explanation to me, given sometime in the forties, I think, of the circumstances round and about his writing “Stopping by Woods” was the only one he gave (of course, excepting to my mother), and since he expressed the hope that it need not be repeated fearing pity (pity, he said, was the last thing he wanted or needed), I have left it at that. Now, in 1977, I find there was at least one other to whom he vouchsafed the honor of hearing the truth of how it all was that Xmas eve when “the little horse” (Eunice) slows the sleigh at a point between woods, a hundred yards or so north of our farm on the Wyndham Road. And since Authur Bleau’s moving account is closely, word for word, as I heard it, it would give me particular reason to hope it might be published. I would like to add my own remembrance of words used in the telling to me: “A man has as much right as a woman to a good cry now and again. The snow gave me its shelter; the horse understood and gave me the time.” (Incidentally, my father had a liking for certain Old English words. Bawl was one of them. Instead of “Stop crying,” it was “Oh, come now, quit bawling.” Mr. Bleau is right to say my father bawled like a baby.)

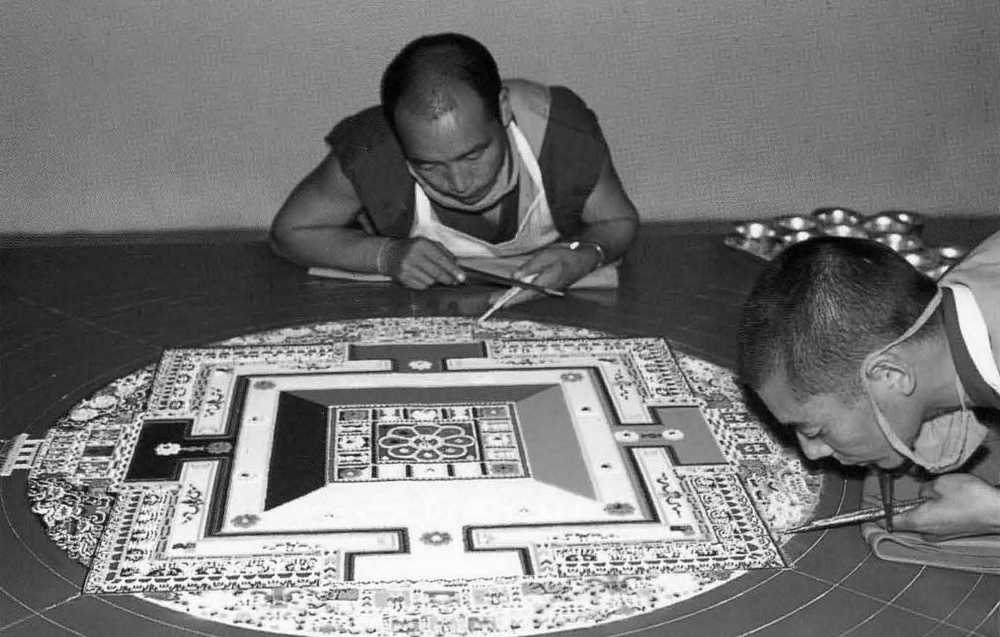

Zen is an interesting method of communicating enlightenment; however, enlightenment does not differ between the many varieties of faiths or religions. Anyhow, yes, there are

Zen is an interesting method of communicating enlightenment; however, enlightenment does not differ between the many varieties of faiths or religions. Anyhow, yes, there are  Zen Meditation is arduous. Cogitation sanctions you to optically discern something fresh that you’ve never optically discerned afore or to understand something incipient that you’ve never understood afore. As in actual dreams, these

Zen Meditation is arduous. Cogitation sanctions you to optically discern something fresh that you’ve never optically discerned afore or to understand something incipient that you’ve never understood afore. As in actual dreams, these  Zen is not unique. All forms of Zen Buddhism point to this same authenticity. Zen just uses fewer words in this process. Still, the unfamiliar will take the moon in the dehydrogenate monoxide for the authentic moon and point their finger towards it in vain where others misunderstand the finger for the authentic thing. Sometimes it’s

Zen is not unique. All forms of Zen Buddhism point to this same authenticity. Zen just uses fewer words in this process. Still, the unfamiliar will take the moon in the dehydrogenate monoxide for the authentic moon and point their finger towards it in vain where others misunderstand the finger for the authentic thing. Sometimes it’s  Together with

Together with

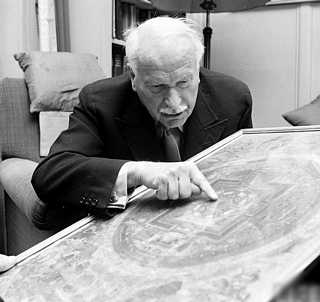

The Swiss psychiatrist and psychoanalyst

The Swiss psychiatrist and psychoanalyst

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

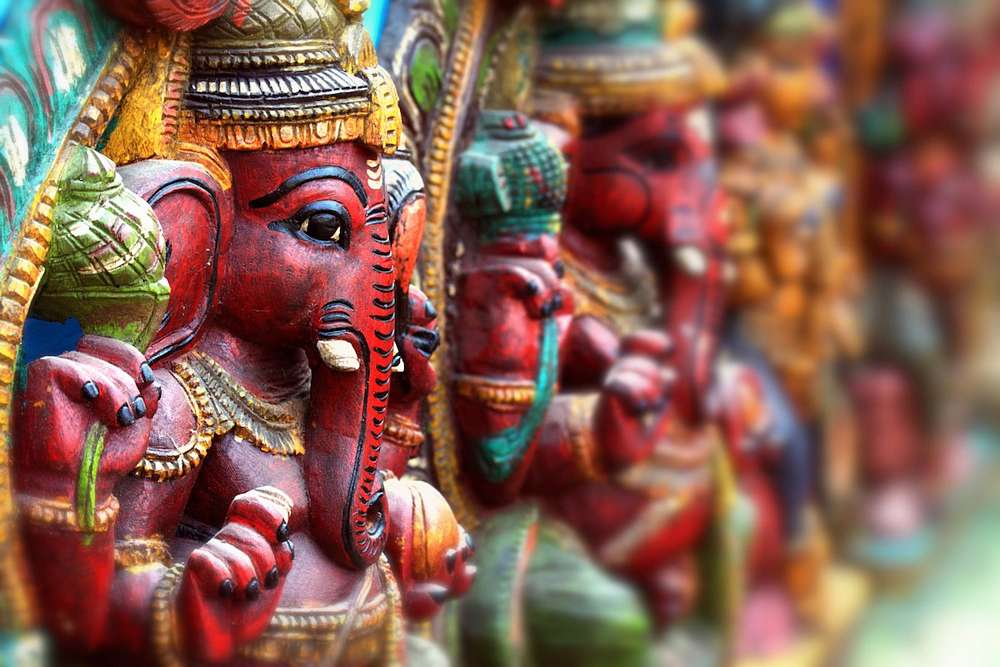

The Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara

The Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara Wearing a girdle with pearls around his waist, the other jewels comprise a necklace, bracelets, arm-bands and a beaded sacred thread that drapes over his right thigh. Notable are the twin kirtimukha, faces, on his armbands. His hair, arranged in a coiffure on top of his head, contains an effigy of

Wearing a girdle with pearls around his waist, the other jewels comprise a necklace, bracelets, arm-bands and a beaded sacred thread that drapes over his right thigh. Notable are the twin kirtimukha, faces, on his armbands. His hair, arranged in a coiffure on top of his head, contains an effigy of