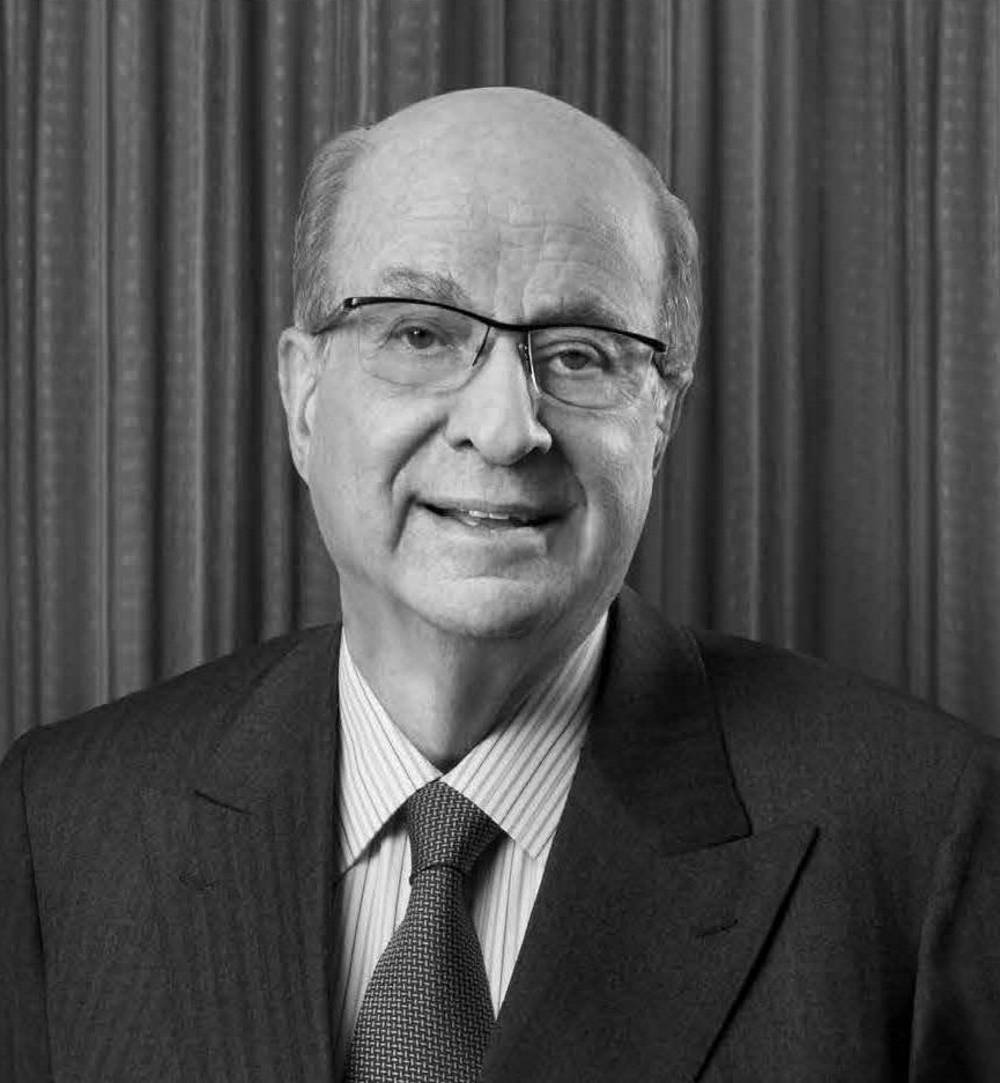

Edgar de Picciotto, an early promoter of hedge fund investing, passed away on Sunday 13 March 2016 after a long sickness. On November 12, 1969, de Picciotto opened his own asset-management bank in a city dominated by such well-known private banking names as Pictet Group, Lombard Odier, Darier and Hentsch.

Edgar de Picciotto founded Union Bancaire Privee (UBP) in 1969. UBP is one of the most favorably capitalized private banks in the world, and a leading player in the field of wealth management in Switzerland with $110 billion in assets under management at the end of December 2015. Edgar de Picciotto, who was born of Syrian-Lebanese parentage, moved to Switzerland in the 1950s and worked as a financier before founding UBP’s predecessor in 1969. From the bank’s inconspicuous headquarters on one of Geneva’s chief luxury-shopping drags, he built a customer base of affluent individuals and institutions all over Europe, the U.S., and the Middle East.

De Picciotto was born in Beirut and hailed from a lineage of businesspersons, which lived from the 14th to the 17th century in Portugal, moving in later centuries via Italy and Syria to the Lebanon. He afterward lived with his parents and brothers in Milan, ultimately deciding to study mechanical engineering in France. However, it was financial engineering, which took his perpetual fancy. He earned his spurs and made financial contacts, working in his previous father-in-law’s bank in Geneva. In its 2015 annual report, UBP recalled,

As our 2015 Annual Report was going to print, we learnt with deep sorrow that Edgar de Picciotto, the Chairman and founder of Union Bancaire Privee, had passed away at 86 years of age.

Edgar de Picciotto was a recognized creative visionary and pioneer in a wide variety of fields in the banking industry. He quickly rose to become a leading figure of the Geneva financial hub, and one of the most respected authorities on investments around the world.

In just a few decades, Edgar de Picciotto turned UBP into one of the world’s biggest family-owned banks. Very early on, he also set up a governance structure designed to ensure the Group’s longevity by integrating the second generation of his family into the business.

UBP is his life’s work. UBP is his legacy to us. It now falls to us to grow UBP with the same entrepreneurial spirit that he used to create the Bank, by perpetuating the values that Edgar de Picciotto would wish to see upheld every day and in everything we do.

Edgar de Picciotto’s children and all the members of UBP’s management are determined to carry on the spirit that its founder instilled in it, and they know that they can rely on the professionalism and dedication of all UBP’s staff members to continue to grow the Bank’s business, while also maintaining its independence.

In 2002, news of merger talks between two family-controlled private banks, Union Bancaire Privee (UBP) and Discount Bank & Trust Company (DTBT) over forming one of Geneva’s biggest private banks became newest sign of the altering attitude among the country’s private banks. Withdrawing from UBP’s operational management 20 years ago, de Picciotto set up a governance structure designed to guarantee the bank’s durability. His son Guy de Picciotto has been chief executive officer since 1998, while his daughter, Anne Rotman de Picciotto, and his eldest son, Daniel de Picciotto, are on the board of directors.

Byron Wien, vice chairperson of Blackstone Advisory Partners, had the pleasure of calling Edgar de Picciotto his mentor.

My purpose in reviewing Edgar’s thinking over the past 15 years is to show how he consistently tried to integrate his world view into the investment environment. That was his imperative. He wasn’t always right, but he was always questioning himself and he remained flexible. When he lost money, it tended to cause minimal pain in relation to his overall assets, and when one of his maverick ideas worked, he made what he called “serious money.”

Edgar de Picciotto as a Mentor

Mentors fall into two categories: there are those you work with every day who are incessantly guiding you to enhanced performance. The ability to serve as a great mentor is one of the most undervalued and underappreciated skills in finance. Perhaps better branded as a “role model,” an outstanding mentor can provide not only a wide-ranging knowledge base and technical skills, but also the sagacious financial judgment that implies the high-class investor. Perhaps of even larger importance, a mentor can express a “philosophy of practice,” including the optimal interaction with clients and economists, a procedure for remaining current with advances in the field, and a thorough concept of how the practice of finance fits into a full life. A sympathetic mentor can also provide counselling in selecting the best practice opportunity and can maintain a close relationship for many years.

Mentors are significant to all of us, as they teach us what can’t be learned from books or in the classroom. They set aside a concrete example of “how to get it done,” and, sometimes more importantly, what to be done, when to do it, and whom to engage in the effort. Their inspiration often carries us through when nothing else does.

- Understand the consequence of understanding the macro environment. “Many people describe themselves as stock pickers … but you have to consider the economic, social, and political context in which the stocks are being picked.” De Picciotto indubitably showed he had a good nose for trends.

- Meet as many people of authority as you can. “For him, networking never stopped.” De Picciotto took great pleasure from knowing smart people and exchanging ideas with them.

- “Nobody owns the truth.” De Picciotto would test his ideas on those he cherished and, and if he ran into a convincing conflicting opinion, he would contemplate on it seriously and sometimes change his position. While he never lacked principle about his ideas, he was unprejudiced and malleable.

- Value the trust and the delight of friendship and the vainness of resentment. De Picciotto was gratified of his own success but also an enthusiast of the success of others who were his friends.

- Never talk about overlooked opportunities except when you are disapproving yourself. Be your own harshest critic. Even if you are an intellectual risk taker, you will make many mistakes. Diagnose them early, but never stop taking risks, because that is where the tangible opportunities are and your life will be more invigorating as a result.

Today, we will dig deeper into his selling discipline. For many investors, buying a stock is much easier than deciding when to sell it. Selling securities is much more difficult than buying them. The average investor often

Today, we will dig deeper into his selling discipline. For many investors, buying a stock is much easier than deciding when to sell it. Selling securities is much more difficult than buying them. The average investor often .jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

In the 06-Dec-1961 (Thursday) edition of

In the 06-Dec-1961 (Thursday) edition of  Berkshire Hathaway’s

Berkshire Hathaway’s

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)