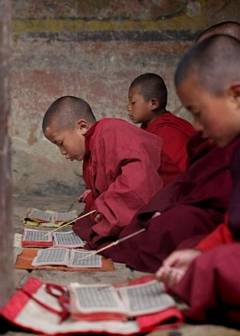

Zen meditation was found to reduce stress and blood pressure, and be efficacious for a variety of conditions, as suggested by positive findings in therapists and musicians. Subliminal processing is frequently thought to be automatic and independent of attention. However, the present framework implies that top-down attention and task set can have an effect on subliminal processing. People respond to arduousness in different ways. Let it ache away. It is for the reason that you choose and reject that you are not free. Zen meditation increases access to unconscious information.

Zen meditation was found to reduce stress and blood pressure, and be efficacious for a variety of conditions, as suggested by positive findings in therapists and musicians. Subliminal processing is frequently thought to be automatic and independent of attention. However, the present framework implies that top-down attention and task set can have an effect on subliminal processing. People respond to arduousness in different ways. Let it ache away. It is for the reason that you choose and reject that you are not free. Zen meditation increases access to unconscious information.

On completing the great supreme dharma, there is the arising of the wisdom of the path of seeing. It has the nature of sixteen moments. There are also other states that are terrifying. Meditation takes gumption. It is certainly a great deal easier just to sit back and watch television. So why bother? Simple. For the reason that you are human. Heavenly states can only be attained by performing meritorious deeds with a minimum of desire. However, the methods themselves are wandering poetic conceptions. If you are really paying attention to the method, you will be aware of a stray thought as soon as it arises. Later, there will be things to learn in other places.”

Zen Koan: “Voice of Happiness” Parable

After Bankei had passed away, a blind man who lived near the master’s temple told a friend:

“Since I am blind, I cannot watch a person’s face, so I must judge his character by the sound of his voice. Ordinarily when I hear someone congratulate another upon his happiness or success, I also hear a secret tone of envy. When condolence is expressed for the misfortune of another, I hear pleasure and satisfaction, as if the one condoling was really glad there was something left to gain in his own world.

“In all my experience, however, Bankei’s voice was always sincere. Whenever he expressed happiness, I heard nothing but happiness, and whenever he expressed sorrow, sorrow was all I heard.”

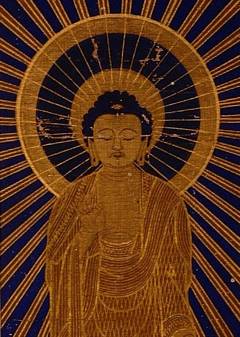

Buddhist Insight on Groundlessness

Groundlessness is the enlightened world, a way of being where concepts like good and evil are empty, without substance, where there is no birth and death, and where everything is interdependent and without abiding form. In addition, it is possible to feel that because one is proficient origin of great suffering this faculty raises one above the insensitive herd. After a little while, he was able to sit up, feeling very much better than he had felt for a long time. In addition, he began to think about why it was he had fainted, and why he was now feeling so much refreshed in body and mind. The American Tibetan Buddhist nun Pema Chodron writes in Buddha’s Daughters,

When things fall apart and we’re on the verge of we know not what, the test for each of us is to stay on the brink and not concretize. The spiritual journey is not about heaven and finally getting to a place that’s really swell. In fact, that way of looking at things is what keeps us miserable. Thinking that we can find some lasting pleasure and avoid pain is what in Buddhism is called samsara, a hopeless cycle that goes round and round endlessly and causes us to suffer greatly.

The very first noble truth of the Buddha points out that suffering is inevitable for human beings as long as we believe that things last – that they don’t disintegrate, that they can be counted on to satisfy our hunger for security. From this point of view, the only time we ever know what’s really going on is when the rug’s been pulled out and we can’t find anywhere to land. We use these situations either to wake ourselves up or to put ourselves to sleep. Right now – in the very instant of groundlessness – is the seed of taking care of those who need our care and of discovering our goodness.

In our most tenebrous times of being disoriented or inundated, there is additionally sapience in reaching out to ask for avail. The mentors, sagacious friends, and guides who

In our most tenebrous times of being disoriented or inundated, there is additionally sapience in reaching out to ask for avail. The mentors, sagacious friends, and guides who

A Zen master may seem insouciant, but

A Zen master may seem insouciant, but  Before enlightenment, people distinguish between a quiescent state, which they call “nirvana,” and a chaotic state, which they call “samsara.” They want to

Before enlightenment, people distinguish between a quiescent state, which they call “nirvana,” and a chaotic state, which they call “samsara.” They want to  Humility in the Zen tradition additionally involves some kind of frolicsomeness, which is a sense of humor. In most religious Zen traditions, you feel self-effacing for the reason that of trepidation of penalization, pain and sin. In the Shambhala world, you feel full of it. You feel salubrious and good. In fact, you feel proud. Consequently, you

Humility in the Zen tradition additionally involves some kind of frolicsomeness, which is a sense of humor. In most religious Zen traditions, you feel self-effacing for the reason that of trepidation of penalization, pain and sin. In the Shambhala world, you feel full of it. You feel salubrious and good. In fact, you feel proud. Consequently, you

.jpg)

Love is the ultimate transgression, bell hooks argues. Its transformative power can shatter the status quo. In Zen Meditation, we develop

Love is the ultimate transgression, bell hooks argues. Its transformative power can shatter the status quo. In Zen Meditation, we develop

Meditation teaches us how to relate to life directly, so we can truly experience the present moment, free from conceptual overlay. Whenever you make distinctions, your mind is in opposition. If your mind is free from the environment, not

Meditation teaches us how to relate to life directly, so we can truly experience the present moment, free from conceptual overlay. Whenever you make distinctions, your mind is in opposition. If your mind is free from the environment, not