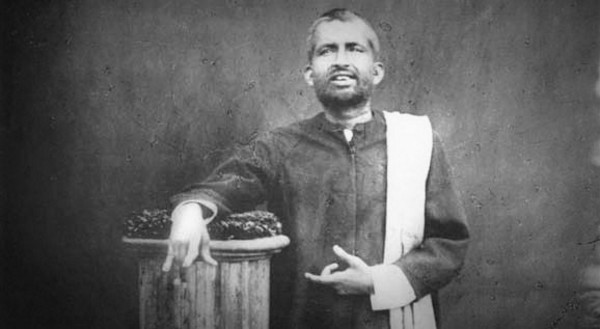

Sri Ramakrishna Paramahamsa (1836–1886,) the eminent Hindu mystic of 19th-century India, used stories and parables to portray the core elements of his philosophy. The meaning of Sri Ramakrishna Paramahamsa’s stories and parables are usually not explicitly stated. The meanings are not intended to be mysterious or confidential but are, in contrast, quite uncomplicated and obvious.

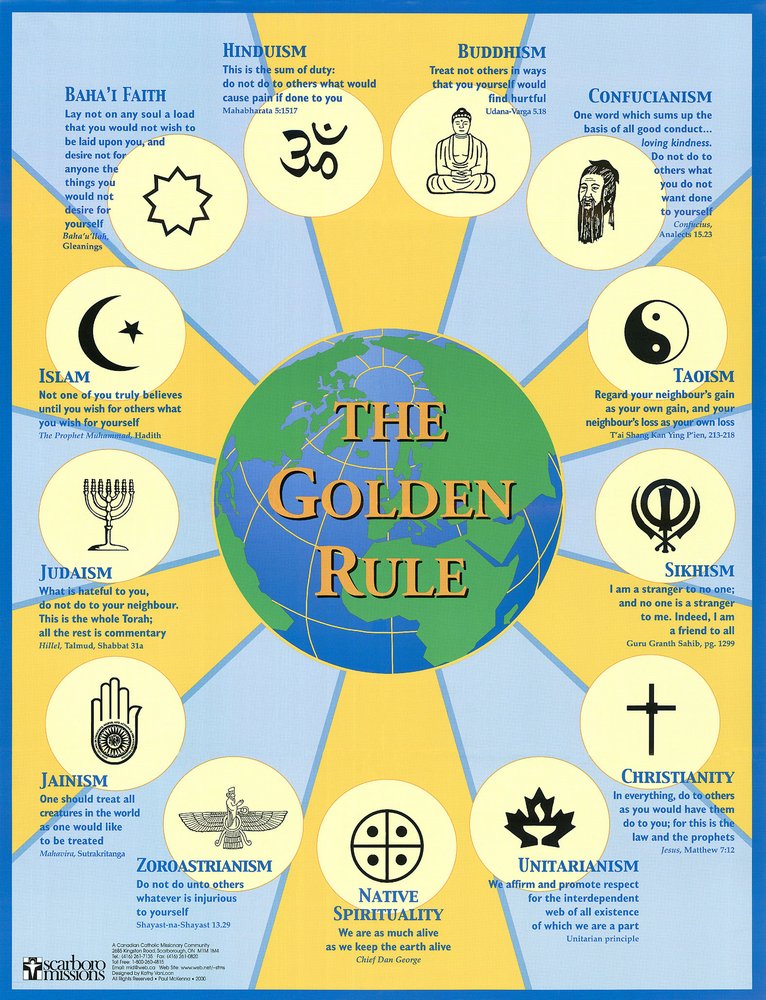

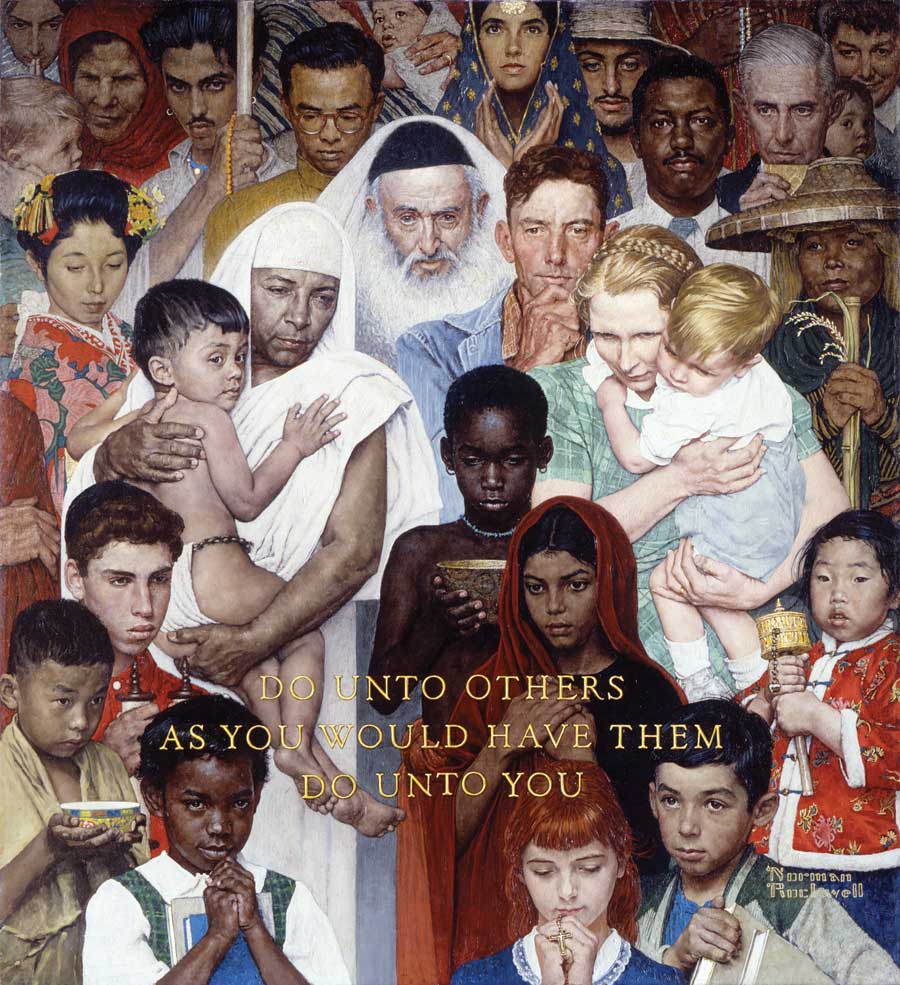

In the Hindu and other traditions of the major religions of the world, parables form the language of the wise for enlightening the simple, just as well as they form the language of the simple for enlightening the wise.

The Parable of Raghuram and Lord Sri Rama’s Will

Raghuram was a pious weaver. He was a devotee of Lord Sri Rama. He firmly believed that everything happens by the will of Lord Sri Rama. The sun shines, the rain falls, the wind blows, men walk, and fish swim – all by the will of Lord Sri Rama. If Lord Sri Rama’s will is not there, everything will come to a standstill. This was Raghuram’s strong faith.

Raghuram never forgot Lord Sri Rama. As soon as he got up early in the morning, he would repeat the name of Lord Sri Rama. After bathing, after offering Naivedyam (offering) to Lord Sri Rama, he would take his breakfast saying, “by the will of Lord Sri Rama.” Again, before starting weaving he would take the name of Lord Sri Rama. As he plied the shuttle, weaving the cloth, he would be chanting Lord Sri Rama’s name. He would take the woven clothes to the bazaar for sale. If someone asked him what the price of a particular cloth was he would say, “By the will of Lord Sri Rama, the yarn costs one rupee. By the will of Lord Sri Rama, my labor costs 50 paisa. By the will of Lord Sri Rama, the profit is 25 paisa. So the price of the cloth, by the will of Lord Sri Rama, is rupees1.75.”

Raghuram’s sincerity and simplicity would charm men and women. No one would bargain with him. They would pay him whatever he demanded. They were sure he would never overcharge them or cheat them.

After the sales were over, Raghuram would return home chanting Lord Sri Rama’s name all the way. He would have his food and go to sleep again taking the Lord’s name.

On one hot and humid day, Raghuram thought he would sit in the verandah of his home for some time. He was chanting ‘Ram, Ram’. A gang of robbers passed that way. They had burgled a rich man’s house. They had a big bundle, which contained lots of cash, jewels, and other valuable articles. They saw Raghuram sitting in the verandah. “Here is a hefty fellow. We can make him carry the heavy bundle. They put the bundle on his head and told him, “Walk with us, or else we shall trash you.”

Raghuram, without any protest, went with them carrying the heavy load. He continued chanting ‘Ram, Ram’ all the way. At the end of the street, three police officers were doing their beats. The robbers got frightened. They ran away.

Raghuram was left alone with the bundle on his head. He did not run away. He stood there chanting ‘Ram, Ram’. The police opened the bundle and discovered the loot. They were happy thinking they had caught the robber red-handed. They marched Raghuram to the police station. He was kept in the lock-up that night. Next morning the police produced Raghuram and the bundle before the Magistrate. They charged Raghuram with the robbery.

The news of Raghuram’s robbery charges quickly spread in the village. Men, women, and children rushed to the court in wonder. “How could he commit any robbery?” they speculated.

The Magistrate also had heard of Raghuram. He too could not associate robbery with this peaceful-looking weaver. However, the police had caught him with the bundle. Anyway, the Magistrate pondered, “I will not punish this man until I am sure he has committed the robbery. Let me ask him for his own explanation.”

The Magistrate asked the prisoner, “Tell the court what exactly happened.”

All the while, Raghuram was standing as if he was in another world. His lips were continuously moving, uttering ‘Ram, Ram’. No one who saw his face would think he was a criminal.

Raghuram now turned to the Magistrate and told him in a clear voice. “Your Lordship, by Lord Sri Rama’s will, I was sitting in my verandah. By Lord Sri Rama’s will, some robbers came that way, By Lord Sri Rama’s will, they put their bundle on by head and made me walk with them. By Lord Sri Rama’s will, there were some police officers ahead. By Lord Sri Rama’s will, the robbers ran away. By Lord Sri Rama’s will, the police arrested me, and kept in the lock-up. By Lord Sri Rama’s will, they have produced me before you. By Lord Sri Rama’s will, you want to punish me.”

Tears began to flow down the cheeks of the magistrate. This man was so utterly like a child. He had nothing to hide. He was not calculating or clever in the usual sense. His trust in God was absolute. He must be not punished but worshipped.

The Magistrate said in open court, “I am convinced this man is innocent. I discharge him. Let him be set free.”

Raghuram joined his palms before the Magistrate and told him, “By Lord Sri Rama’s will, you have set me free.”

The huge crowd assembled in the court shouted “Jai Ram, Victory to Lord Sri Rama.” They took him procession back to his home.

Sri Ramakrishna Paramahamsa once said, “More are the names of God and infinite are the forms through which He may be approached. In whatever name and form you worship Him, through them you will realize Him.”

Recommended Books

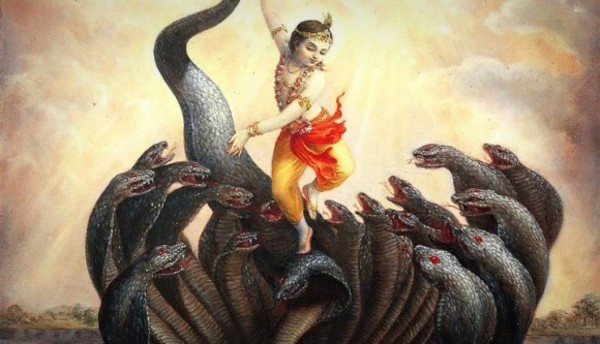

In the Hindu mythology, the nagas reside within the earth in an aquatic underworld. They are embodiments of terrestrial waters as well as door-and gate-custodians. In terms of significance, the nagas are creatures of abundant power who defend the underworld and confer fertility and prosperity upon those with which they are individually associated in the worldy realm—a meadow, a shrine, a temple, or even a whole kingdom.

In the Hindu mythology, the nagas reside within the earth in an aquatic underworld. They are embodiments of terrestrial waters as well as door-and gate-custodians. In terms of significance, the nagas are creatures of abundant power who defend the underworld and confer fertility and prosperity upon those with which they are individually associated in the worldy realm—a meadow, a shrine, a temple, or even a whole kingdom.

In

In  In

In