![]()

With only $538 as investment in 1938, a time when the long fingers of the Great Depression still stuck the nation by its financial gullet, two aspiring entrepreneurs named Bill Hewlett and David Packard used a one-car garage as a part-time workshop in Palo Alto, California, to birth a company intended to become a world leader in engineering measurement and computer technology. From such unpretentious beginnings, the two Stanford University alumnae and close friends molded an organization that for half a century would outpace its competitors through groundbreaking products, progressive employee policies, and an enduring commitment to quality and customer satisfaction.

In 1938, Dave Packard left his job at General Electric in New York and returned to Palo Alto while Hewlett looked for a place to set up shop. Hewitt found a great place in suburbs, with the 12×18 foot garage the main selling point of the property on Addison Avenue. The home had a three-room, ground floor flat for Packard and his wife Lucille, while Hewlett got the shed out back. The rent was $45 per month.

In 1989, during the 50th anniversary of the recognized Hewlett-Packard corporation, the State of California termed the one-car garage first used as a workspace by Bill Hewlett and David Packard in Palo Alto as the “birthplace of Silicon Valley.” This historic landmark also represents the beginning of innovation, chance taking, and common sense policies in a company that would bourgeon as few have before or since.

367 Addison Avenue in Palo Alto, California, is the house and one-car garage—dubbed the “birthplace of Silicon Valley”—where William (Bill) Hewlett and David Packard began making their first product in 1939. Mr. Packard died in 1996, Mr. Hewlett in 2001. HP bought the property in 2000, 13 years after the garage was designated California Registered Landmark No. 976.

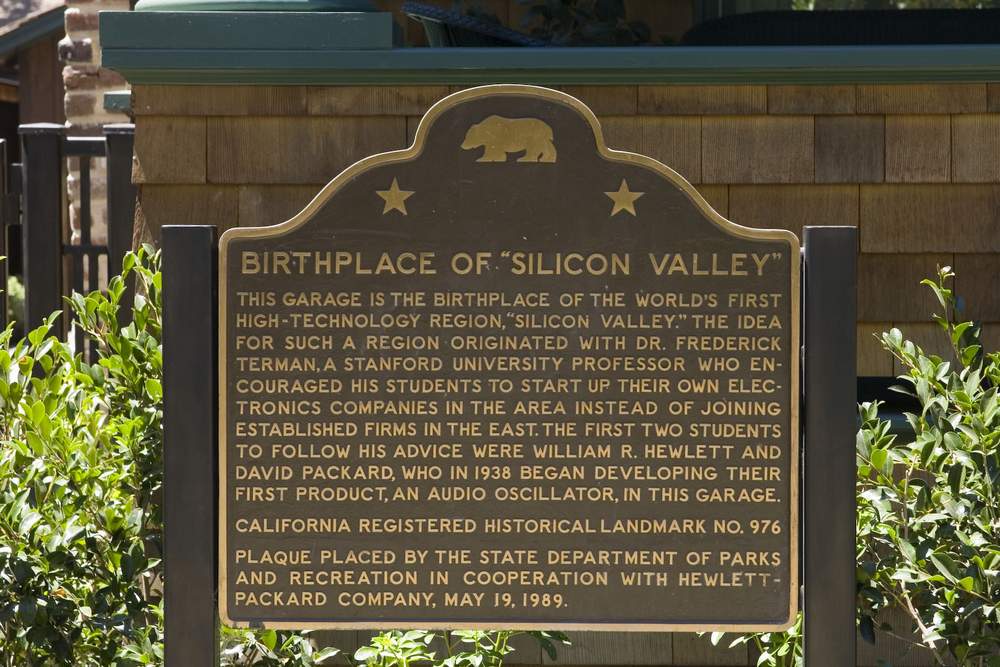

This garage is the birthplace of the world’s first high-technology region, “Silicon Valley.” The idea for such a region originated with Dr. Frederick Terman, a Stanford University professor who encouraged his students to start up their own electronics companies in the area instead of joining established firms in the East. The first two students to follow his advice were William R. Hewlett and David Packard, who in 1938 began developing their first product, an audio oscillator, in this garage.

California Registered Historical Landmark No. 976

Plaque placed by the State Department of Parks and Recreation in cooperation with Hewlett-Packard Company, May 19, 1989.

The Hewlett-Packard House and Garage is also National Register Listing 07000307.

Although the garage has become Silicon Valley legend, Hewlett and Packard only stayed at the garage a mere 18 months. The company was officially founded in 1939, with HP outgrowing the garage by 1940. The company moved to a larger property nearby on Page Mill Road. The garage was bestowed the honour of the birthplace of Silicon Valley in 1989, with HP buying the property in 2000.

Two years ago, the blood-testing startup

Two years ago, the blood-testing startup