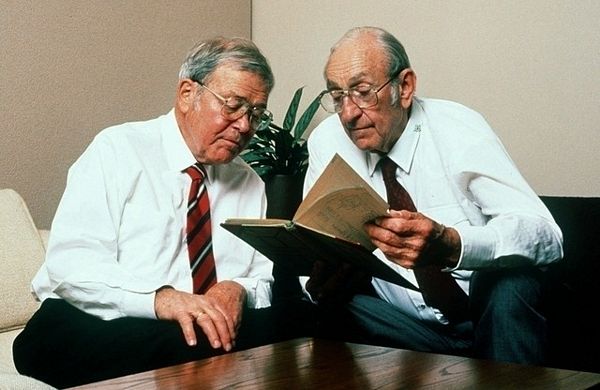

Dave Packard, along with Bill Hewlett, friend and fellow graduate of electrical engineering from Stanford University, started Hewlett-Packard (HP) in Packard’s Palo Alto garage with an initial capital investment of US$538. Bill Hewlett and Dave Packard are known for their legendary people-oriented management style and community consciousness.

Below are eleven simple rules that reflected Dave Packard’s philosophy of work and life. These rules were first presented by Dave Packard at HP’s second annual management conference in 1958 in Sonoma, California. A memo containing these seven simple rules was discovered in Dave’s correspondence file.

- Build up the other person’s sense of importance. When we make the other person seem less important, we frustrate one of his deepest urges. Allow him to feel equality or superiority, and we can easily get along with him.

- Respect the other man’s personality rights. Respect as something sacred the other fellow’s right to be different from you. No two personalities are ever molded by precisely the same forces.

- Give sincere appreciation. If we think someone has done a thing well, we should never hesitate to let him know it. WARNING: This does not mean promiscuous use of obvious flattery. Flattery with most intelligent people gets exactly the reaction it deserves—contempt for the egotistical “phony” who stoops to it.

- Eliminate the negative. Criticism seldom does what its user intends, for it invariably causes resentment. The tiniest bit of disapproval can sometimes cause a resentment which will rankle—to your disadvantage—for years.

- Avoid openly trying to reform people. Every man knows he is imperfect, but he doesn’t want someone else trying to correct his faults. If you want to improve a person, help him to embrace a higher working goal—a standard, an ideal—and he will do his own “making over” far more effectively than you can do it for him.

- Check first impressions. We are especially prone to dislike some people on first sight because of some vague resemblance (of which we are usually unaware) to someone else whom we have had reason to dislike. Follow Abraham Lincoln’s famous self-instruction: “I do not like that man; therefore I shall get to know him better.”

- Take care with the little details. Watch your smile, your tone of voice, how you use your eyes, the way you greet people, the use of nicknames and remembering faces, names and dates. Little things add polish to your skill in dealing with people. Constantly, deliberately think of them until they become a natural part of your personality.

- Develop genuine interest in people. You cannot successfully apply the foregoing suggestions unless you have a sincere desire to like, respect and be helpful to others. Conversely, you cannot build genuine interest in people until you have experienced the pleasure of working with them in an atmosphere characterized by mutual liking and respect.

- Keep it up. That’s all—just keep it up!

For Bill Hewlett and Dave Packard’s legendary management style and the history of Hewlett Packard, read ‘Bill & Dave: How Hewlett and Packard Built the World’s Greatest Company’ by Michael S. Malone and ‘The HP Way: How Bill Hewlett and I Built Our Company’ by David Packard.

Source: HP Retiree Website