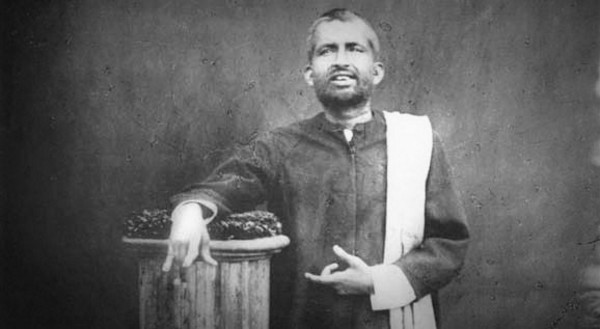

Sri Ramakrishna Paramahamsa (1836–1886,) the eminent Hindu mystic of 19th-century India, used stories and parables to portray the core elements of his philosophy. The meaning of Sri Ramakrishna Paramahamsa’s stories and parables are usually not explicitly stated. The meanings are not intended to be mysterious or confidential but are, in contrast, quite uncomplicated and obvious.

In the Hindu and other traditions of the major religions of the world, parables form the language of the wise for enlightening the simple, just as well as they form the language of the simple for enlightening the wise.

The Parable of Devicharan and Sarvamangala

In a village, there once lived a poor Brahmin named Devicharan.

Devicharan was a very good man and he loved the Mother of the universe with all his heart. He worshipped the Mother in the form of Durga.

Very often, people asked Devicharan to go and read to them about the Mother from a book called the Chandi. In return, they gave him gifts of food or clothing. In this way, Devicharan was able to get enough to eat. He lived happily with his wife and daughter, and although they were so poor, they never felt sad.

Devicharan’s daughter was very beautiful and very good. Her name was Sarvamangala. Her parents taught her all they knew and she learned everything very quickly. She worked hard and whatever she did, she did well.

The time came when Sarvamangala was old enough to be married.

“You must look for a husband for your daughter,” Sarvamangala’s mother said to Devicharan. “But who will marry such a poor girl? We have nothing to give her.”

“Do not be anxious, my dear,” Devicharan replied.”

“Our daughter is as beautiful as Lakshmi and as gifted as Saraswati. Where is there a girl as lovely and as brilliant as Sarvamangala?”

“You are right,” agreed his wife. “She is good and beautiful, and skillful in everything she does. Her cooking is excellent. Above all, she loves to make people happy by serving them.”

“So we must not worry, about her marriage,” Devicharan said. “Mother Durga will do everything.”

A few weeks later, a good man who was a landlord paid a visit to the village, and he happened to see Sarvamangala. When he found that she was as good as she was beautiful he wanted her to be married to his son.

Devicharan agreed to this and Sarvamangala was married. She went away to her father-in-law’s house in the next village.

Devicharan and his wife felt sad and lonely, without their daughter, but they were happy that she was no longer poor and had a good husband.

Soon it was the month of the Durga Puja festival.

“Wife,” said Devicharan,” “Mother Durga has blessed our daughter with a good and wealthy husband. This year we must perform Durga Puja in our own house.”

“But, we are so poor” his wife replied. “We have barely enough to eat ourselves, how can we think of-doing the Puja here?”

“What?” cried Devicharan. “Is Durga the Mother of the rich and not of the poor? Will she not accept our humble offerings? We shall offer her whatever we can afford.”

The time of the festival drew near.

“We must bring home the image of the Mother,” Devicharan said to his wife.

“I wish Sarvamangala could come home, too,” his wife replied.

Devicharan took a fifty-paisa coin and went to the image-maker.

“I am going to perform Durga Puja in my house,” Devicharan said. “Please make me a small image of Durga. I shall pay you fifty paisa.”

“Have you lost your senses, Devicharan Babu?” the image-maker replied. “It costs a great deal of money to perform Durga Puja, and even the smallest image costs more than fifty paisa.”

“I have no money,” Devicharan explained, “but I love the Mother and I am grateful to her. I shall perform Durga Puja even if I worship her with nothing but flowers.”

The image-maker looked very surprised, and he became thoughtful.

“I understand your feelings,” he said. “Very well, I shall make an image for you, and you need not pay me for it.”

“I must pay you whatever I can afford,” Devicharan answered, and he made the man accept the fifty paisa.

As Devicharan and his wife prepared for the Puja, their thoughts turned very often to their daughter. Sometimes they wept because they felt so lonely without her.

“She will not be allowed to come to us now,” Devicharan said, “because she will be too busy. In that rich family they will perform Durga Puja in a big way and Sarvamangala will be a great help to them. We shall have to manage without her.”

The next day, however, Devicharan’s wife fell ill.

“What shall we do?” she wept. “Tomorrow the Puja begins, but I am too ill to move from my bed. Who will cook? Who will help us? Oh, Sarvamangala, we need you.”

Devicharan comforted his wife. “Don’t regret,” he said. “I shall go at once and see Sarvamangala. Perhaps her father-in-law will allow her to come, as you are ill.”

Devicharan went to Sarvamangala’s home, but she was not allowed to go back with him.

“I am very sorry,” her father-in-law said to Devicharan, “but my wife just cannot manage without her.”

Feeling sad and worried, Devicharan said good-bye to his daughter, and set out for home. He talked to Mother Durga as he walked along.

“The image-maker has made a beautiful image for me,” he said, “and tomorrow I want to worship you. Now my wife is ill and my daughter cannot come home. What am I to do?”

At that moment, Devicharan heard someone calling him from behind. It seemed to be his daughter’s voice. He stopped and looked back. To his surprise there was Sarvamangala hurrying towards him.

“Wait for me, Father,” Sarvamangala cried, “I am coming home with you.”

“How is it possible for you to come?” cried Devicharan. “What will your mother-in-law say?”

“Do not worry about anything, Father,” Sarvamangala replied. “Everything is arranged. Take me home with you.”

Now Devicharan and his wife were very happy. Their daughter had come home. She seemed more beautiful than ever and her face was bright with joy. She took care of her mother and did all the work of the house.

The same evening Sarvamangala helped her father to dress the image of Durga for the worship, which would begin the next day. The image stood in a decorated shrine and when they had finished they were amazed at its beauty. Sarvamangala’s mother now felt much better and she too praised the image.

“See how beautifully Sarvamangala has dressed the image,” she said. “And see how beautiful Sarvamangala is herself. We have no costly silks and jewels, yet our goddess and our daughter will find no equal anywhere for charm and beauty.”

The first two days of the festival passed happily. Devicharan worshipped Durga and his heart was filled with peace. The third day came, and this was the day when guests should be fed.

“Today we must give a feast to all the neighbors,” Sarvamangala said.

“Are you joking, child?” Devicharan replied. “How is it possible for us to give a feast? We have only a few fruits to offer.” “I am not joking, Father,” Sarvamangala said. “You have worshipped the Mother in your house. The worship will not be complete if you do not give a feast. I am going now to invite all the neighbors.”

Sarvamangala went to the neighbors’ houses. Devicharan prepared for the worship.

“Now that my daughter is married to a rich man’s son,” Devicharan thought, “she thinks” it is easy to give a feast.”

When Sarvamangala returned, Devicharan sat down to worship the goddess. Sarvamangala assisted him. The image seemed to be living and Devicharan’s face shone with joy. The whole room seemed to shine with light from the goddess.

At noon, the neighbors began to arrive. Sarvamangala had invited them all to partake of the fruit offerings made to the Mother.

“Just see what a prank the girl has played,” Devicharan said, feeling very worried.

“We shall look very foolish when they find we have nothing to offer them,” his wife said.

“Now you are both to stop worrying,” Sarvamangala said firmly. “Leave it all to me. I have invited them and I shall give them the offerings.”

Devicharan welcomed all the guests, and then went and sat before the Mother. “Let me not be put to shame, Mother,” he said. He remained sitting before the image for now he was afraid to face the guests.

Sarvamangala asked the guests to sit down, and then she served the fruit that had been offered to Durga during the worship.

“My father is poor,” Sarvamangala said, “so he cannot give you a big feast. It is his good fortune that you have come and request you to partake of these offerings.”

The guests began to eat the fruit.

“What delicious fruit!” they exclaimed. “We have never tasted anything like it. Just a little of it is quite satisfying. This is better than a big feast.”

With great happiness, the guests went home. They showered their good wishes and blessings upon Sarvamangala and her parents.

“Have the guests all gone?” Devicharan asked. “Did they laugh at me or curse me?”

“Nothing of the kind,” Sarvamangala said. “They were all very happy indeed.”

“The strange thing is,” Sarvamangala’s mother said, “half the offerings still remain, yet the guests were completely satisfied.” “It is indeed strange,” Devicharan said. “Mother has blessed us,” he added, and tears of joy flowed down his cheeks.

The following day was the last day of the worship. Devicharan felt sad, for today the Mother would leave his house. He sat before the image, offering the goddess a special dish made of rice, curds, and fruit.

As Devicharan sat there with his eyes closed he did not notice Sarvamangala enter the room. Quietly she began to eat the food that was being offered to the goddess. Then Devicharan opened his eyes. He was shocked to see his daughter eating the offering.

“What are you doing, daughter?” he cried.

Without saying a word, Sarvamangala ran from the room.

Devicharan asked his wife to prepare a fresh offering, and when it was ready, he again sat down to worship the Mother.

Again Sarvamangala crept into the room and ate up the food that was being offered, and again Devicharan asked his wife to prepare some more.

For the third time Sarvamangala crept into the room and ate up all the offering. Now Devicharan felt angry with her.

“What is wrong with you today?” he cried. “Do not spoil my worship again. Go away.”

Sarvamangala went to her mother.

“Father told me to go away, Mother,” she said, “so I am going.”

“Today you will have to go back to your father-in-law’s house, child,” her mother replied, “for the festival is over. When your father has finished the worship he will take you home.”

When Devicharan at last finished the Puja, he went to his wife.

“Where is Sarvamangala?” he asked.

“She was here a short while ago,” his wife replied. “She must be waiting for you to take her home.”

They searched and searched for Sarvamangala, but could not find her anywhere.

“The foolish girl must have gone alone to her father-in-law’s house,” Devicharan said. “I must go and see that she is safe.”

When Devicharan reached the house, he was relieved to see that his daughter was there.

“I scolded you for spoiling the worship,” he said to her. “Is that why you came away alone? Are you very angry with me?”

“What are you talking about, Father?” Sarvamangala replied looking very puzzled.

“Did you not eat up the offering as I was doing the Puja?” Devicharan said. “Did I not scold you?”

“But, Father, I have been here all the time,” Sarvamangala replied. “My father-in-law told you I could not go with you.”

Devicharan was astonished. Then he understood what had happened.

It was Durga herself who had come in the form of his daughter.

“Mother, Mother,” he cried, weeping tears of joy. “You came to me and I did not know you!”

Sri Ramakrishna Paramahamsa once said, “I see God walking in every human form. When I meet different people, I say to myself, ‘God in the form of the saint, God in the form of the sinner, God in the form of the righteous, God in the form of the unrighteous’.”

Recommended Books

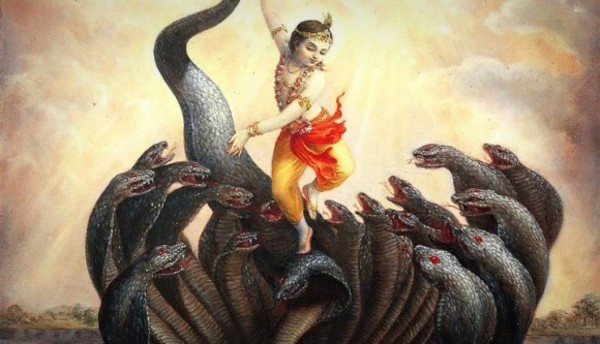

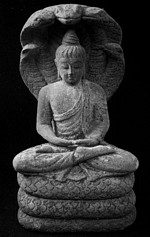

In the Hindu mythology, the nagas reside within the earth in an aquatic underworld. They are embodiments of terrestrial waters as well as door-and gate-custodians. In terms of significance, the nagas are creatures of abundant power who defend the underworld and confer fertility and prosperity upon those with which they are individually associated in the worldy realm—a meadow, a shrine, a temple, or even a whole kingdom.

In the Hindu mythology, the nagas reside within the earth in an aquatic underworld. They are embodiments of terrestrial waters as well as door-and gate-custodians. In terms of significance, the nagas are creatures of abundant power who defend the underworld and confer fertility and prosperity upon those with which they are individually associated in the worldy realm—a meadow, a shrine, a temple, or even a whole kingdom.