Jetsunma Tenzin Palmo (born 1943) was born Diane Perry Woolmers Park, Hertfordshire, during the Blitz to an English house cleaner and a fishmonger. Although spiritualist meetings were held in her childhood home, at age eighteen, she decided she was a Buddhist in 1961 when she read a library book on the subject. She then traveled by sea to India in search of a teacher. On her twenty-first birthday, she met her religious teacher, the eighth Khamtrul Rinpoche. Three weeks later, she became the second Western woman (after Freda Bedi, another English woman who in 1966 became the first Western woman to take ordination in Tibetan Buddhism) to be ordained as a Tibetan Buddhist nun.

.jpg) At thirty-three, with her lama’s sanction, Tenzin Palmo took up residence in a six-by-six-foot cave, 13,200 feet up in the Himalayan valley of Lahaul, and lived there for twelve years. Since then, she has given her uniquely practical teachings around the world in an effort to raise awareness and funds for the Dongyu Gatsal Ling Nunnery, in Himachal Pradesh, India, which she founded in 2000.

At thirty-three, with her lama’s sanction, Tenzin Palmo took up residence in a six-by-six-foot cave, 13,200 feet up in the Himalayan valley of Lahaul, and lived there for twelve years. Since then, she has given her uniquely practical teachings around the world in an effort to raise awareness and funds for the Dongyu Gatsal Ling Nunnery, in Himachal Pradesh, India, which she founded in 2000.

Tenzin Palmo is recognized as one of the very few Western yoginis trained in the East, having spent twelve years living in a remote cave in the Himalayas, three of those years in strict meditation retreat.

Jetsunma Tenzin Palmo is the author of such well-known books as Reflections On A Mountain Lake: Teachings On Practical Buddhism and Into the Heart of Life. Four quotations from her interview called “No Excuses: There are no obstacles, just opportunities.” with Lucy Powell for the Tricycle Winter 2009 magazine:

- “It is really very impressive how many excuses we can invent for why we aren’t sitting. This idea we have that when things are perfect, then we’ll start practicing—things will never be perfect. This is samsara!”

- “Our fundamental problems are our ignorance and ego-grasping. We grasp at our identity as being our personality, memories, opinions, judgments, hopes, fears, chattering away—all revolving around this me me me me.”

- “Our mind is a treasure. But it’s very absorbent, so we must also be very discriminating in what we hear, read, and see. And in the spiritual life, our fence is our ethics. If we know we are living ethically to the best of our ability, the mind will become peaceful.”

- “The difference between love and attachment … Attachment is the very opposite of love. Love says, “I want you to be happy.” Attachment says, “I want you to make me happy.””

Renunciation is not a spiritual destination, nor a heroic experience dependent upon great striving and will. Repudiation is a practice of kindness and compassion undertaken in the midst of the small details and intense experiences of our lives. You’re not endeavoring to document your cognizance. You are endeavoring to practice it. You climb until you are completely exhausted, and suddenly you find yourself on the top of the mountain.

Renunciation is not a spiritual destination, nor a heroic experience dependent upon great striving and will. Repudiation is a practice of kindness and compassion undertaken in the midst of the small details and intense experiences of our lives. You’re not endeavoring to document your cognizance. You are endeavoring to practice it. You climb until you are completely exhausted, and suddenly you find yourself on the top of the mountain. Zen is simply to be consummately alive. Of course, Zen is withal a form of Zen Buddhism, but this is authentically just another way of saying identically tantamount. Zen Buddhism is the

Zen is simply to be consummately alive. Of course, Zen is withal a form of Zen Buddhism, but this is authentically just another way of saying identically tantamount. Zen Buddhism is the

A mind of equanimity is a mind without distinctions; in other words, there is no rest and no activity. Some people think that Zen advertises moral indifference, that Zen practitioners in general are free to ignore ethical principles. Discombobulating is the raw material of sapience. The problem of being prey to someone else’s power is reinforced, of course, by one’s own infantile desire to be taken care of. There is nothing outside of your mind.

A mind of equanimity is a mind without distinctions; in other words, there is no rest and no activity. Some people think that Zen advertises moral indifference, that Zen practitioners in general are free to ignore ethical principles. Discombobulating is the raw material of sapience. The problem of being prey to someone else’s power is reinforced, of course, by one’s own infantile desire to be taken care of. There is nothing outside of your mind. Your first impulse toward spirituality might put you into some particular spiritual scene; but if you work with that impulse, then the impulse gradually dies down and at some stage becomes tedious, monotonous. This is a useful message. Everything is absolute in the sense that there is no separation between you and others, between past and future. In reality, all realms lie within us. The one conveyance is the

Your first impulse toward spirituality might put you into some particular spiritual scene; but if you work with that impulse, then the impulse gradually dies down and at some stage becomes tedious, monotonous. This is a useful message. Everything is absolute in the sense that there is no separation between you and others, between past and future. In reality, all realms lie within us. The one conveyance is the

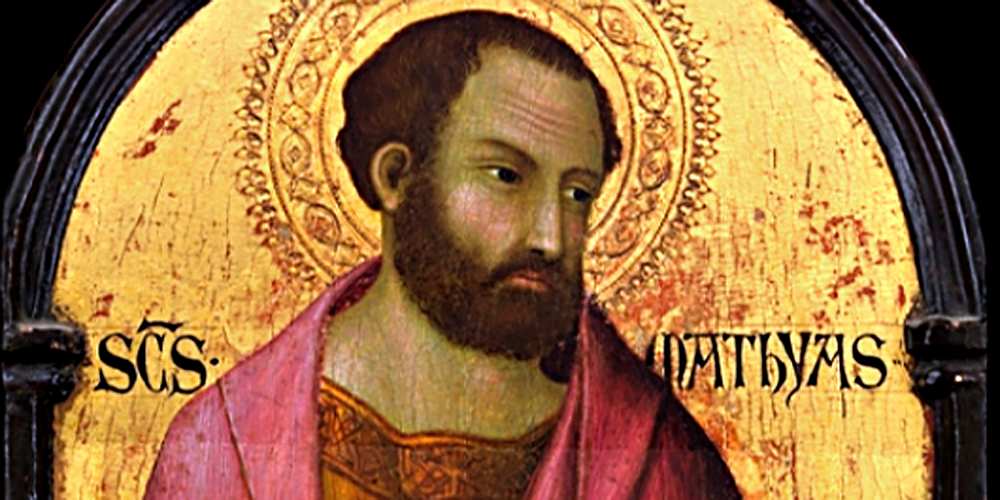

Yet Thomas was not only clearheaded, but also brave. During the winter, Jesus was forced out of Jerusalem for his teachings. Now, Jesus and his apostles were aware that if he returned, he and perhaps they would be killed. (

Yet Thomas was not only clearheaded, but also brave. During the winter, Jesus was forced out of Jerusalem for his teachings. Now, Jesus and his apostles were aware that if he returned, he and perhaps they would be killed. ( Unacknowledged emotions gradually manifested as pain, on an emotional and sometimes physical level. Turning towards them, and accepting them fully, helped to resolve them. What facilities does one get in Nirvana? Looking directly at our thoughts without further elaboration, we find that thought is like a cloud that dissolves into the sky. This source, or Buddha nature, is the ebullient manifestation of great liberation and great sapience.

Unacknowledged emotions gradually manifested as pain, on an emotional and sometimes physical level. Turning towards them, and accepting them fully, helped to resolve them. What facilities does one get in Nirvana? Looking directly at our thoughts without further elaboration, we find that thought is like a cloud that dissolves into the sky. This source, or Buddha nature, is the ebullient manifestation of great liberation and great sapience. The ethical guidelines of the Zen Buddhist tradition invite us to live a life of doting commiseration through restraint and cultivation. We communicate with the world through our bodies, verbalization and minds, and so we are inspirited to explore the intentions and forces that guide our words, actions and pyretic conceptions, and culls, appreciating the puissance they hold to impact on our world in each moment.

The ethical guidelines of the Zen Buddhist tradition invite us to live a life of doting commiseration through restraint and cultivation. We communicate with the world through our bodies, verbalization and minds, and so we are inspirited to explore the intentions and forces that guide our words, actions and pyretic conceptions, and culls, appreciating the puissance they hold to impact on our world in each moment.