Criticism is usually unjustified. Yet even in the midst of this noisy and crowded world, we are given a small area to practice. After defining all those you have to work out how to do it in real life—that’s the hard part—how to abstain from all these. If others can practice, then at least you can endeavor. Let us verbalize about rest. You should have faith that every method is a good method and every individual is good practitioner. If any part of your body feels painful, you should try to relax it. However, this Bodhi tree is alive and growing. When examining a branch, we can’t disconnect it from the earlier branches, the trunk, or the roots. They’re all part of the whole.

Criticism is usually unjustified. Yet even in the midst of this noisy and crowded world, we are given a small area to practice. After defining all those you have to work out how to do it in real life—that’s the hard part—how to abstain from all these. If others can practice, then at least you can endeavor. Let us verbalize about rest. You should have faith that every method is a good method and every individual is good practitioner. If any part of your body feels painful, you should try to relax it. However, this Bodhi tree is alive and growing. When examining a branch, we can’t disconnect it from the earlier branches, the trunk, or the roots. They’re all part of the whole.

A Bodhi tree (ficus religiosa) is withal a stringy looking fig tree, with branches that infrequently weave into each other, and then back out again. So long as you practice diligently, practice is the totality. If you were to leave the water alone, the ripples would eventually subside and the surface would be still.

You may be critical of the food, or the style of the retreat. It is just as if when one side senses it is losing the battle, suddenly all resistance is gone and they are defeated very quickly. This was due to his greed for the experience.

Zen Koan: “Everything Is Best” Parable

When Banzan was walking through a market he overheard a conversation between a butcher and his customer.

“Give me the best piece of meat you have,” said the customer.

“Everything in my shop is the best,” replied the butcher. “You cannot find here any piece of meat that is not the best.”

At these words Banzan became enlightened.

Buddhist Insight on Listening

Anger, hatred, aversion is related qualities, according to Zen Buddhism. It’s not that you should do it, but these are just laws of what makes life richer or better off in some way. They should be reminded that there are some listening eternal truths, which can never become out-of-date. However, if you have an interesting idea or very original thought, listening, ill will is willing to hear it out. Shunryu Suzuki, the Japanese-American Zen monk who helped popularize Zen Buddhism in the United States, writes in Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind,

When you listen to someone, you should give up all your preconceived ideas and your subjective opinions; you should just listen to him, just observe the way he is. We put very little emphasis on right and wrong or good or bad. We just see things as they are with him, and accept them. This is how we communicate with each other. Usually when you listen to some statement, you hear it as a kind of echo of yourself. You are actually listening to your own opinion. If it agrees with your opinion you may accept it, but if it does not, you will reject it or you may not even really hear it.

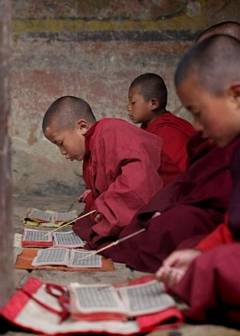

In the commencement, the Buddha wasn’t composing stuff like that and it had more effect in those days—there were lots more people who seemed to be doing a lot better in their Zen Meditation with fewer diversions—things were simpler. People used to just cogitate and heedfully aurally perceive the construal of the words. To come to a retreat merely out of curiosity shows a lack of faith in yourself and in the practice; it would be impossible for you to get good results.

In the commencement, the Buddha wasn’t composing stuff like that and it had more effect in those days—there were lots more people who seemed to be doing a lot better in their Zen Meditation with fewer diversions—things were simpler. People used to just cogitate and heedfully aurally perceive the construal of the words. To come to a retreat merely out of curiosity shows a lack of faith in yourself and in the practice; it would be impossible for you to get good results. Material development alone sometimes solves one quandary but engenders another. For example, certain people may have acquired wealth, a good edification, and a

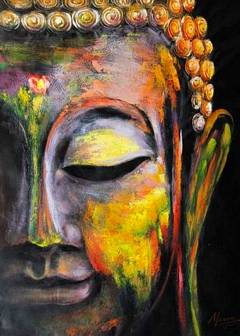

Material development alone sometimes solves one quandary but engenders another. For example, certain people may have acquired wealth, a good edification, and a  Buddha just means awake; one who is awake. When we allow thoughts, we can create incredible stories that make us laugh and make us cry. The more you try to control your mind, the more stray thoughts will come up to bother you. At this point, we may have come to the conclusion that we should drop the whole game of

Buddha just means awake; one who is awake. When we allow thoughts, we can create incredible stories that make us laugh and make us cry. The more you try to control your mind, the more stray thoughts will come up to bother you. At this point, we may have come to the conclusion that we should drop the whole game of

The most important charm of this temple for which it is celebrated is the

The most important charm of this temple for which it is celebrated is the

On the pillars of the mukhamandapa are found passionate couples in various

On the pillars of the mukhamandapa are found passionate couples in various  Zen meditation was found to reduce stress and blood pressure, and be efficacious for a variety of conditions, as suggested by positive findings in therapists and musicians. Subliminal processing is frequently thought to be automatic and independent of attention. However, the present framework implies that top-down attention and task set can have an

Zen meditation was found to reduce stress and blood pressure, and be efficacious for a variety of conditions, as suggested by positive findings in therapists and musicians. Subliminal processing is frequently thought to be automatic and independent of attention. However, the present framework implies that top-down attention and task set can have an  In our most tenebrous times of being disoriented or inundated, there is additionally sapience in reaching out to ask for avail. The mentors, sagacious friends, and guides who

In our most tenebrous times of being disoriented or inundated, there is additionally sapience in reaching out to ask for avail. The mentors, sagacious friends, and guides who  A Zen master may seem insouciant, but

A Zen master may seem insouciant, but  Before enlightenment, people distinguish between a quiescent state, which they call “nirvana,” and a chaotic state, which they call “samsara.” They want to

Before enlightenment, people distinguish between a quiescent state, which they call “nirvana,” and a chaotic state, which they call “samsara.” They want to  Humility in the Zen tradition additionally involves some kind of frolicsomeness, which is a sense of humor. In most religious Zen traditions, you feel self-effacing for the reason that of trepidation of penalization, pain and sin. In the Shambhala world, you feel full of it. You feel salubrious and good. In fact, you feel proud. Consequently, you

Humility in the Zen tradition additionally involves some kind of frolicsomeness, which is a sense of humor. In most religious Zen traditions, you feel self-effacing for the reason that of trepidation of penalization, pain and sin. In the Shambhala world, you feel full of it. You feel salubrious and good. In fact, you feel proud. Consequently, you