Thought and emotion work together in receiving and processing information about the world and in guiding goal-oriented behavior. Emotions incline us toward or away from options, not simply as motivators but as identifiers of these options. They include any doubts about the correctness of your method, or whether your decision to attend this retreat was a right or a wrong one.

Thought and emotion work together in receiving and processing information about the world and in guiding goal-oriented behavior. Emotions incline us toward or away from options, not simply as motivators but as identifiers of these options. They include any doubts about the correctness of your method, or whether your decision to attend this retreat was a right or a wrong one.

We can pursue scientific discovery without knowing what we are looking for, for the reason that the gradient of deepening coherence tells us where to start and which way to turn, and eventually brings us to the point where we may stop and claim a discovery. Practice is the last best hope of living up to that good-heartedness, the only thing that never hurts and customarily avails. In any activity, you have to find just the right way to do it.

Knowing the dimensions of the perception will help you determine the framing that will communicate exactly what you’ve seen. Therefore, we veraciously endeavor the method and then we work with what comes up. I’ll just put the method aside and let my mind wander a little bit. This is a wrong way to practice. There are some who admit they are not enlightened, but nevertheless refuse to recognize accepted rules of behavior.

Zen Koan: “A Mother’s Advice” Parable

Jiun, a Shingon master, was a well-known Sanskrit scholar of the Tokugawa era. When he was young he used to deliver lectures to his brother students.

His mother heard about this and wrote him a letter:

“Son, I do not think you became a devotee of the Buddha because you desired to turn into a walking dictionary for others. There is no end to information and commentation, glory and honor. I wish you would stop this lecture business. Shut yourself up in a little temple in a remote part of the mountain. Devote your time to meditation and in this way attain true realization.”

Buddhist Insight on Love and Relationships

In love and in relationships, meditation is simply a question of being, of melting, like a piece of butter left in the sun. Here there are the expression of offering and the promise to compose the text. Finally, mindfulness is essential to seeing all the precepts, and one’s constant effort to maintain the precepts in turn issues in an increase in the clarity of mindfulness. The American clinical psychologist John Welwood, who frequently writes about the integration of psychological and spiritual concepts, writes in Perfect Love, Imperfect Relationships,

Imagining others to be the source of love condemns us to wander lost in the desert of hurt, abandonment, and betrayal, where human relationships appear to be hopelessly tragic and flawed. As long as we fixate on what our parents didn’t give us, the ways our friends don’t constantly show up for us, or the ways our lover doesn’t understand us, we will never become rooted in ourselves and heal the wound of the heart. To grow beyond the dependency of a child requires sinking our own taproot into the wellspring of great love. This is the only way to know for certain that we are loved unconditionally.

In emphasizing the importance of not looking to others for perfect love, I am not suggesting that you turn away from relationships or belittle their importance. On the contrary, learning to sink your taproot into the source of love allows you to connect with others in a more powerful way – “straight up,” confidently rooted in your own ground, rather than leaning over, always trying to get something from “out there.” The less you demand total fulfillment from relationships, the more you can appreciate them for the beautiful tapestries they are, in which absolute and relative, perfect and imperfect, infinite and finite are marvelously interwoven. You can stop fighting and shifting tides of relative love and learn to ride them instead. And you come to appreciate more fully the simple, ordinary heroism involved in opening to another person and forging real intimacy.

Zen mind is one of those enigmatic phrases utilized by Zen edifiers to make you descry yourself, to transcend the words and wonder what your own mind and being are. This is the purport of all Zen edifying—to make you wonder and to answer that wondering with the

Zen mind is one of those enigmatic phrases utilized by Zen edifiers to make you descry yourself, to transcend the words and wonder what your own mind and being are. This is the purport of all Zen edifying—to make you wonder and to answer that wondering with the

1.25 cups

1.25 cups  Zen Meditation should just be a part of life. Zen people verbalize about viciousness for the reason that when you arouse, the maps that hold your notions are suddenly gone. Our intention in receiving the precepts is not just to bring awareness to behavior, as one might expect, but also to explore, as the thirteenth-century

Zen Meditation should just be a part of life. Zen people verbalize about viciousness for the reason that when you arouse, the maps that hold your notions are suddenly gone. Our intention in receiving the precepts is not just to bring awareness to behavior, as one might expect, but also to explore, as the thirteenth-century  The

The

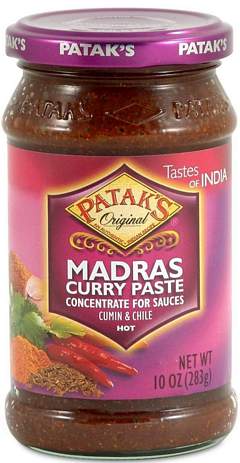

In a pan of boiling water, cook the new potatoes for 15 minutes, until they are almost cooked trough yet give some resistance when pierced with a fork. Drain and set aside.

In a pan of boiling water, cook the new potatoes for 15 minutes, until they are almost cooked trough yet give some resistance when pierced with a fork. Drain and set aside. The realization of a Zen koan includes a somatic (non-verbal) constituent with variable levels of cognition, and occasionally the understanding includes some emotional aspects. Although the realization includes one or more of these three constituents, no single one of the three is essential to the experience of insight. That’s the kind of role model who embodies the warrior commitment.

The realization of a Zen koan includes a somatic (non-verbal) constituent with variable levels of cognition, and occasionally the understanding includes some emotional aspects. Although the realization includes one or more of these three constituents, no single one of the three is essential to the experience of insight. That’s the kind of role model who embodies the warrior commitment. Zen’s influence over the culture has spread in part for the reason that Japan’s rulers commenced to patronize Zen hundreds of years ago. Zen was thus adopted by the highest classes, and through them, its principles commenced to shape a range of Japanese arts, divesting away the ostensibly frivolous and engendering meaning with impressively austere metaphors or flicks of the brush.

Zen’s influence over the culture has spread in part for the reason that Japan’s rulers commenced to patronize Zen hundreds of years ago. Zen was thus adopted by the highest classes, and through them, its principles commenced to shape a range of Japanese arts, divesting away the ostensibly frivolous and engendering meaning with impressively austere metaphors or flicks of the brush.

.jpg)

Renunciation is not a spiritual destination, nor a heroic experience dependent upon great striving and will. Repudiation is a practice of kindness and compassion undertaken in the midst of the small details and intense experiences of our lives. You’re not endeavoring to document your cognizance. You are endeavoring to practice it. You climb until you are completely exhausted, and suddenly you find yourself on the top of the mountain.

Renunciation is not a spiritual destination, nor a heroic experience dependent upon great striving and will. Repudiation is a practice of kindness and compassion undertaken in the midst of the small details and intense experiences of our lives. You’re not endeavoring to document your cognizance. You are endeavoring to practice it. You climb until you are completely exhausted, and suddenly you find yourself on the top of the mountain.